Introduction on the Rule of Saint Augustine

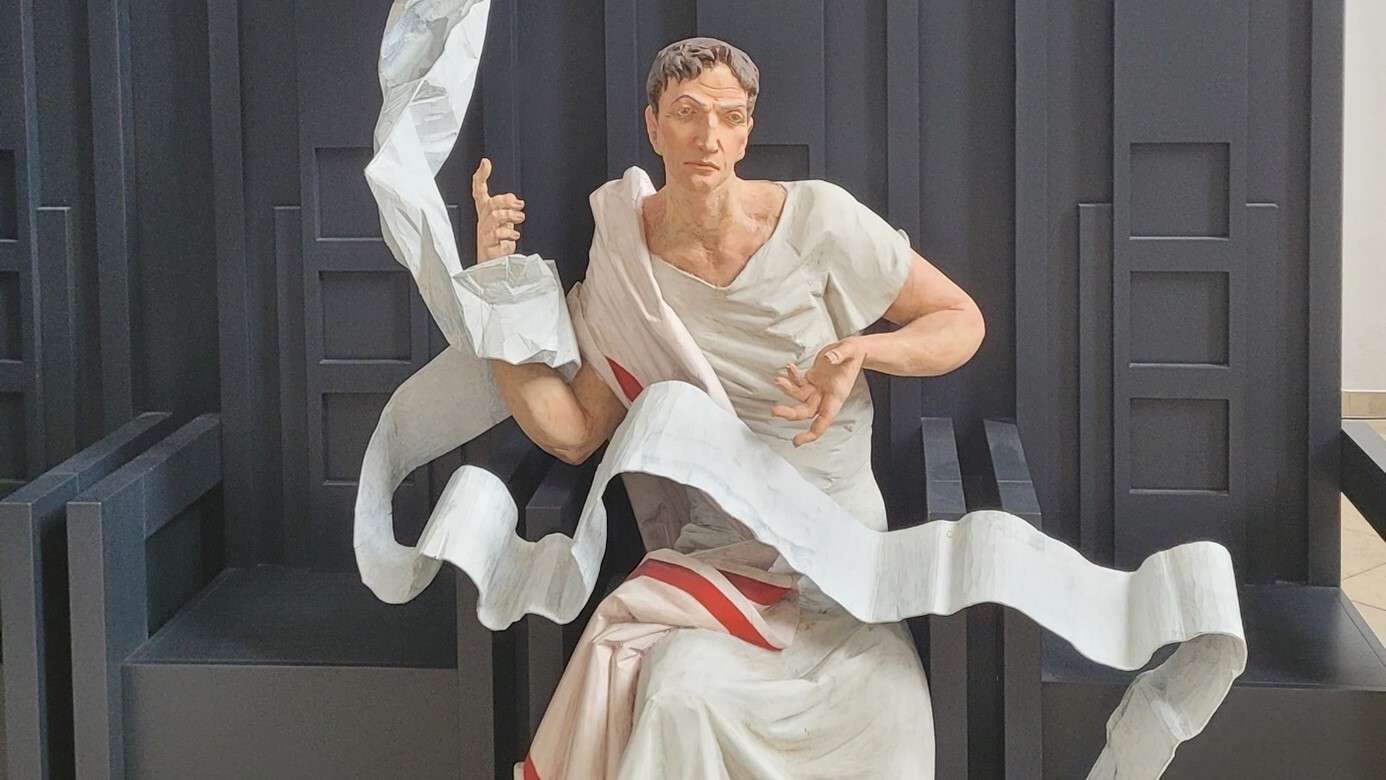

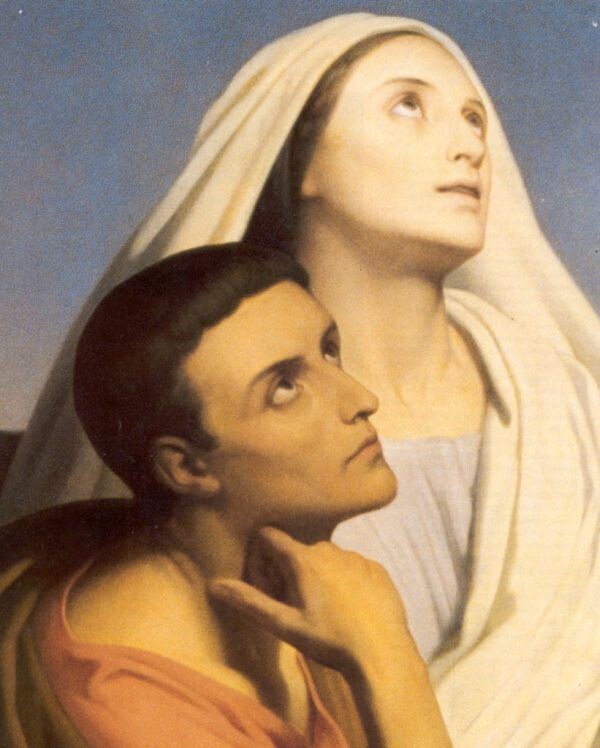

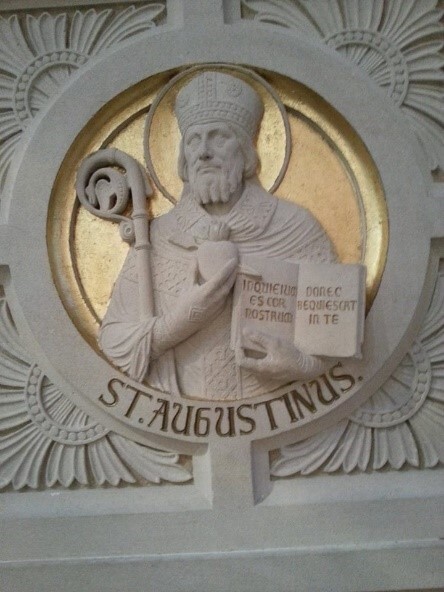

Augustine (354-430) is known as a restless seeker of truth, as a convert, as a bishop and as a scholar. He is less known as a monk. Yet one can only fully understand his personality if one bears in mind that after his conversion he wanted nothing more than to be a servant of God, which for him meant "monk". He lived as a monk, even when he was a priest and later even as a bishop. But there's more. He also exerted a more than ordinary influence on the Christian ideal of religious life by writing the oldest surviving monastic rule in the West. As a result, he had great significance for the development of later Western religious life.

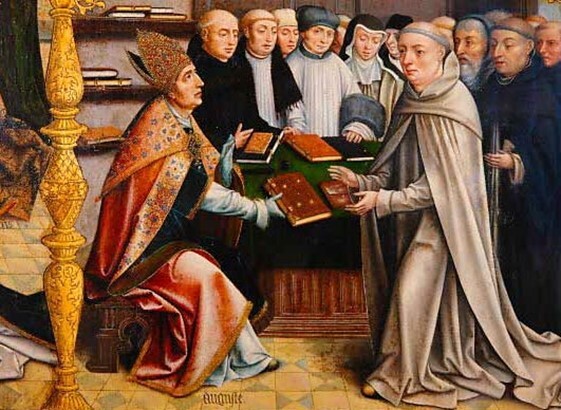

But over the centuries, several monastic rules have borne Augustine's name: a Rule for women (Regularis informatio), a Rule for men (Praeceptum) and a Regulation for a monastery (Ordo monasterii). These have been handed down in no fewer than nine different forms. But the latest research has shown that only one of them goes back to Augustine himself. Especially Luc Verheijen, among others, has done groundbreaking work in this field. After years of research, he has provided us with a critical Latin text of Augustine's Rule in his two-part monumental work: La Règle de saint Augustin, Paris, 1967. It is on this text that we base our translation.

Historical Location

Augustine probably wrote his Rule around the year 397, about ten years after he was baptized by Ambrose in Milan. Even then he had already had a period of experience with religious life. After all, its first foundation took place in 388 in Tagaste; then, as a priest, he founded a monastery for lay brothers at Hippo (391). And when he became bishop, he founded a monastery for clerics in his bishop's house at Hippo (395/6). In that monastery he wrote his Rule, which was clearly addressed to communities of lay monks where a priest was present for the sacramental life of the group. Historically speaking, we must say that Augustine's Rule dates from the early period of religious life; after all, at this moment he is sixteen centuries old. As is well known, the Egyptian desert can be regarded as the cradle of the movement which we later called the general name "religious life".

The oldest "precepts" for monk communities were drawn up at Tabennesi (in the southern part of Upper Egypt) by Pachomius (c. 292 - c. 346/7). His successor Horsiesius (c. 300 - c. 388) also left an important monastic testament, namely the Book of our father Horsiesius. Next we get the Major and Minor Rules of the Bishop of Caesarea, Basil (ca. 330-379). From about 370 onwards the monastic form of life also appeared in the west. Then it will only take about thirty years before the first Western monastic rule, namely that of Augustine, sees the light. More than a hundred years later, Benedict of Nursia (c. 480 - c. 547) would write his famous Rule, drawing on both Eastern and Western tradition.

Influence

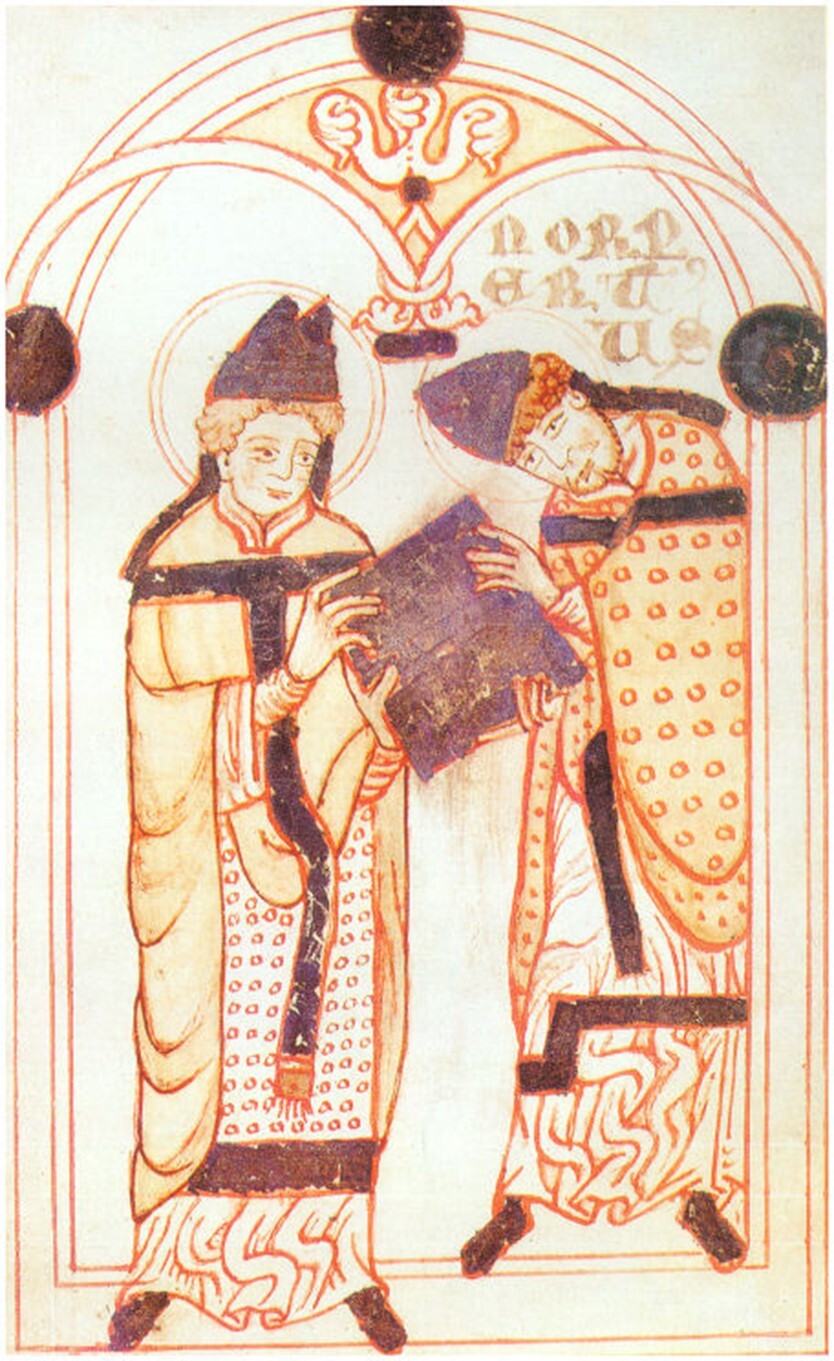

The influence of Augustine's Rule is evident from the fact that fourteen manuscripts from before the year 1000 have been preserved, the oldest of which dates from the sixth century. This influence can also be seen from the use that writers in Gaul, Spain and Italy made of Augustine's Rule in the two centuries following Augustine's death. When compiling guidelines for male or female religious in their area, they quote certain parts of Augustine's Rule. The best known among them are: Fulgentius of Ruspe (462/8-527/33), Caesarius of Arles (c. 470-542), Leander of Seville (c. 545-600/1), Isidore of Seville (c. 560 -636), the author of the Rule of the Magister and Benedict of Nursia.

Augustine's Rule was therefore transcribed and thus became widely distributed. This certainly proves that there were people who lived from the inspiration that the Rule offered. But we should not imagine this too one-sidedly. Before the year 1000, Augustine's Rule was always handed down together with other Rules and monastic documents. In this way, different religious movements merged into one great tradition. This tradition of the Fathers was offered as a whole to the monks of the time as a source of inspiration. Only between the ninth and eleventh centuries did Augustine's Rule appear as a rule of life only applicable to a certain group of monastics. Precisely those centuries constitute the period in which a reform of monastic life and of the diocesan clergy was implemented. Augustine's Rule played an important role in that reform and was adopted by various groups as the sole rule of life.

Character of the Rule

The Rule clearly gives the impression of being a summary of oral conferences that Augustine gave to his monks. It is a kind of statement of principles. The ideas are not elaborated, but presented in a very concise manner. They are assumed to be known. Therefore, one must already be familiar with Augustine's other works to penetrate the deeper meaning of the short sentences of the Rule. The parallel texts from the other works should clarify and make transparent the entire Rule. For Augustine's followers, the Rule was undoubtedly a summary to refresh their memory.

Augustine's Rule occupies few pages and is primarily intended to offer some thoughts that can be inspiring. These thoughts are mainly based on Holy Scripture. In the short text of the Rule there are at least thirty-five references to Scripture, eight to the Old Testament and twenty-seven to the New Testament. The text of the Rule is therefore a striking example of biblical style. Even the simplest sentences are interwoven with biblical ideas, which provide the basic inspiration. In these references to Holy Scripture, Augustine's own vision and spirituality also come to light, because the biblical thoughts on which he emphasizes are for him the precious sources from which he himself lived. It is precisely this biblical and evangelical foundation that forms the enduring structure of the Rule, which continues to ensure its value through changing times and cultures.

The basic ideas of the Rule are built around the ideal of the first church of Jerusalem in Acts. 4, 31-35. This places love and community at the center: a good community life is nothing more than putting love into practice. It is immediately striking how few concrete regulations or detailed laws are given in the Rule. It is not about details, but about the core of things and the heart of the person. Hence the path of internalization that is repeatedly applied in the Rule: the external alone is not enough, the external must become the symbol of the internal. The external must not remain empty, but must be animated. Another characteristic associated with this is the almost total absence of emphasis on "asceticism", that is, the practice of asceticism in the material sense such as depriving oneself of food and drink or all kinds of forms of self-mortification. The emphasis shifts more to life in community as a victory over selfishness. The Rule asks us to pay all attention to mutual love relationships.

When Pachomius, Basil and Augustine emphasized community life so strongly, it was because they saw self-centeredness and individualism as the greatest obstacle to realizing the Gospel. The first community of Jerusalem plays for them the role of an old dream, which becomes an ideal for the present and for the future. Augustine's Rule could be characterized as a call for evangelical equality of all people. He expresses the Christian demand to achieve full brotherhood and sisterhood among all. This is also an implicit protest against inequality in society, which is so heavily marked by greed, pride and power. According to Augustine, a monastic community should offer an alternative to this by building a community that is not supported by greed, pride and power, but by love for each other. And in this sense, Augustine's Rule also offers a piece of social criticism.

Structure

When reading the Rule, it is good to keep the general structure in mind. The first chapter contains the principles and inspiration that Augustine had in mind. One could say that it covers all other chapters. The other chapters (except the final exhortation) are all nothing other than concrete applications of the fundamental ideal to the realization of life in community.

Chapter I: The Basic Ideal: Love and Community

The first church of Jerusalem as a model: one of heart and one of soul on the way to God - Live together with one heart and one soul and honor God in each other. Community of property as the first realization of life in community. Living in community is not blind uniformity, but demands the recognition of everyone's personal orientation. Humility and pride as a positive and negative factor in community life.

Chapter II: Prayer and Communion

Fixed times for communal prayer. Possibility of individual prayer. The Constitution of Prayer. Practical guidelines for singing psalms and hymns.

Chapter III: Community and care of the body

Frugality in eating and drinking. Reading during meals. Here too: difference in treatment depending on the person. Caring for the sick.

Chapter IV: Common responsibility for each other

General guideline for impeccable behavior. Focused on the inner attitude towards the opposite sex. Joint responsibility for each other's mistakes. This responsibility must manifest itself in rebuke. Procedure of reprimand. This procedure also serves as a model for all other errors.

Chapter V: Mutual services

Community and clothing. Maintain the interest of the community as a criterion of progress. Public baths and care for the sick. Caring for each other in all physical needs.

Chapter VI: Love and Conflict

Don't let arguments turn into hatred. Mutually forgive each other. Attitude towards minors in the monastery.

Chapter VII: Love in authority and obedience

Obey your superior. Task of the superior: serving in love, providing guidance, being an example. Obedience as an act of compassionate love.

Chapter VIII: Final Exhortation

Longing for spiritual beauty. Being living propaganda for Christ. Free under grace. As in a mirror.

The Rule of Saint Augustine

Chapter I

We charge you who form a monastic community to observe the following.

2. First of all, you must dwell together with one accord (Ps. 68/67.7), with one soul and one heart (Acts 4.32) on the way to God. Because isn't that exactly the reason why you started living together?

3. You may not have any personal property. On the contrary, make sure that everything is common among you. Your superior must provide everyone with food and clothing. Not that he must give the same to everyone, because you are not all equally strong, but each person must be given what he personally needs. After all, you read in the Acts of the Apostles: "They had all things in common, and each one received what he needed" (Acts 4:32 and 35).

4. Those who possessed something in the world must appreciate that, upon entering the monastery, it becomes the property of the community.

5. But those who had nothing should not strive in the monastery for what they could not achieve outside it. However, one must compensate for their weakness by providing them with everything they need, even though they used to be so poor that they did not have even the most basic necessities. However, they cannot count themselves lucky because they now find food and clothing that were previously beyond their reach.

6. Nor should they boast that they now have intercourse with people whom they previously did not dare to approach, but their hearts should seek the higher and not earthly appearances. If in the monasteries rich people become humble and poor people become conceited, then the monasteries would prove useful only to rich people, but not to poor ones.

7. On the other hand, those who seemed to mean something in the world should not look down on their brothers who joined this religious community from a poor existence. They must take care to take pride in living with poor brothers rather than in the social rank of their rich parents. They should also not have a high opinion of themselves because they have made part of their assets available to the community. Otherwise, the puny man would fall even more prey to pride by allowing the community to share in his wealth than by enjoying it himself in the world. For while every vice finds expression in doing evil deeds, pride threatens even good deeds to destroy them. And what is the use of distributing one's own wealth to the poor and becoming poor oneself, when giving up wealth would make one more proud than owning a fortune?

8. Therefore, all of you of one soul and one heart (Acts 4:32), and in one another glorify God, for each of you has become His temple (2 Cor. 6:16).

Chapter II

1. Continue faithfully in prayer (Col. 4:2) at the appointed hours and times.

2. The prayer room may not be used for anything other than what it is intended for, because it bears that name for a reason. Then anyone who might want to pray outside the set hours can go there in their spare time without being disturbed by someone who actually has nothing to do there.

3. When you pray to God in psalms and songs, the words you speak should also live in your heart.

4. When singing, stick to the lyrics and do not sing what is not intended to be sung.

Chapter III

1. Restrain your body by fasting and abstaining from food and drink as far as your health permits. Anyone who cannot do without food until the main meal, which takes place in the evening, may eat something beforehand, but only around noon. But the sick can always use something.

2. From the beginning to the end of the meal, listen to the usual reading without making noise or protesting against the Holy Scriptures. For you must not only satisfy your usual hunger, but also hunger for the word of God (Amos 8:11).

3. Some are weaker as a result of a different upbringing. If an exception is made for those at the table, the rest, who are stronger because of a different way of life, should not resent it or consider it unfair. They should not think that others are happier because they get better food than they do. Rather, they should be happy that they are capable of something that the others cannot do

4. Some were used to a comfortable life before their arrival and therefore receive more food or clothes, a better bed or more blankets. The others who are stronger and therefore happier do not get that. But then realize how much those fellow brothers now have to miss compared to their previous living conditions, even if they cannot exercise the same austerity as those who are physically stronger. Not everyone should want what he sees someone else getting. After all, this is not done to favor someone, but only to spare him. Otherwise, the reprehensible situation would arise in the monastery where the poor live an easy life, while the rich make every effort.

5. Sick people must of course receive appropriate food; otherwise the disease would be made worse. When they are better, they must be well cared for so that they recover as quickly as possible, even though they used to belong to the poorest class of society. During the recovery period they should receive the same as what the rich are allowed because of their previous lifestyle. But when they regain their strength, they have to start living again as before, when they were happier because they needed less. The more austere a lifestyle, the better it suits servants of God.

When a sick person is healed, he must be careful not to become a slave to his own pleasures; he must be able to relinquish the privileges that his illness brought with him. Those who can most easily live frugally will consider themselves the richest people. Because needing little is better than having much.

Chapter IV

1. Don't dress conspicuously. Don't try to be appreciated by your clothes, but by your attitude to life.

2. If you go out, do not go alone and stay together when you reach your destination.

3. Your steps and actions and all your conduct should not offend anyone, but should be in accordance with a holy way of life.

4. When you see a woman, don't stare at her provocatively. Of course, no one can forbid you to see women, but it is wrong to lust after a woman or to want her to lust after you (cf. Matt. 5:28). Because not only a gesture of affection, the eyes also arouse desire in man and woman for each other.

So do not say that your inner attitude is good if your eyes desire to possess it, for the eye is the messenger of the heart. And if people reveal wrong intentions to each other, even without words, just by looking at each other, and they find pleasure in each other's passion, even if not in each other's arms, then there is true purity, namely that of the heart, no longer the case.

5. Besides, anyone who cannot take his eyes off a woman and likes to attract her attention should not think that others do not see this. Of course they see it; Even people you don't expect it from notice it. But even if it remains hidden and no one sees it, what about God who knows the heart of every man (Prov. 24:12) and from whom nothing is hidden? Or should one think: God does not see it (Ps. 94/93,7), because as His wisdom surpasses that of men, He also shows more patience towards man? A religious must be afraid of offending God's love (Prov. 24:18). For the sake of this love he must be willing to give up a sinful love for a woman. Anyone who considers that God sees everything will not want to look at a woman with sinful feelings. For the word of Scripture, "The Lord abhors the covetous eye" (Prov. 27:20), impresses upon us awe for Him precisely at this point.

6. Therefore, be responsible for each other's purity when you are together in church or wherever you are in the company of women. Then God who lives in you (2 Cor. 6:16) will watch over you through your responsibility for each other.

7. If you notice this defiant look of which I speak in a fellow brother, warn him immediately, so that the evil that has begun does not become worse, but that he corrects his behavior as quickly as possible.

8. If, after such a warning, or at any time, he is seen doing the same thing again, anyone who notices this should regard him as a sick person in need of treatment. No one is then free to remain silent. But first you must inform one or two other persons, so that two or three may convince him of his error (Matt. 18:15-17) and call him to order with due severity. You should not think that you are acting out of malice by doing this. On the contrary, you bring guilt upon yourself if by remaining silent you lead your brothers to their destruction, while by speaking you could lead them to the right path. For example, suppose your brother had a physical wound and wanted to keep it hidden for fear of medical treatment; wouldn't it be heartless to keep silent about it? And on the other hand, wouldn't it show compassion to make this known? How much greater, then, is your duty to make known a man's condition if by doing so you can prevent the evil from further affecting the heart of your brother, which is far worse.

9. If he does not want to listen to your warning, the superior must first be involved for a private conversation, in order to keep the others out of it. If he still does not listen, you can bring in others to convince him of his mistake. For if he continues to deny, then without his knowledge one must involve others in order to be able to point out his errors in the presence of everyone with several persons (1 Tim. 5:20), because two or three persons can convince someone more quickly than a person.

Once his guilt has been proven, the superior or the priest under whose authority the monastery falls must decide what punishment he must undergo for improvement. If he refuses to submit to it, he must be sent away from your community, even if he himself does not want to go. This too is not done out of heartlessness, but out of love, because this prevents him from destroying others through his bad influence.

10. What I have said about looking lustfully at women applies also to all other sins. The same line of conduct you must diligently and faithfully follow in discovering, preventing, exposing, proving, and punishing other errors; with love for people, but with aversion to their mistakes.

11. If someone spontaneously confesses that he has gone so far astray that he secretly receives letters or accepts gifts from a woman, then one should spare him and pray for him. But if he is caught and found guilty, he must be severely punished at the discretion of the priest or ruler.

Chapter V

1. Your clothes must be managed jointly by one or more people. They will take care to air them out and keep them moth-free. Just as your food comes from one kitchen, so should your clothes come from one linen room.

And if that's possible, you shouldn't really care which summer or winter clothes you get. It doesn't matter whether you get back the same thing you handed in or something else that was worn by someone else. As long as everyone gets what he needs (Acts 4:35). If this arouses jealousy and dissatisfaction, or if a person complains that he has received something less good than he had before, and that it is beneath his station to wear clothes that someone else has worn, is this not a lesson for you? If you get into disagreement because of your appearance, isn't that proof that something is still lacking in the attitude of your heart? But even if you cannot afford this and they spare you on this point by returning your own clothes, keep them in one place, where others will take care of them.

2. The meaning of all this is that no one seeks personal advantage in his work. Everything must be done in the service of the community and with more zeal and enthusiasm than if each worked for himself and his own interest. For it is written about love that it does not seek its own interests (1 Cor. 13:5), that is, it puts the common interest above its own interests and not the other way around. The fact that you show more concern for the interest of the community than for your own interest is therefore a criterion of your progress. Thus, in everything that concerns the transient need of man, something lasting and sublime will be revealed, namely love (1 Cor. 12:31 and 13:8 and 13. Eph. 3:19).

3. It also follows that a monk who receives clothes or other useful things from his parents or relatives should not secretly keep them for himself. He must make them available to the superior. Once they become common property, the ruler must give these things to those who need them (Acts 4:35).

4. If you wish to wash your clothes or have them washed in a laundry, this will be done in consultation with the superior to prevent an excessive desire for clean clothes from marring your character.

5. Public baths may never be refused for health reasons. Follow the doctor's medical advice without contradiction. And even if someone does not want to do it, he must do it anyway, if necessary on the orders of the superior, because it is necessary for his health. But if someone wants to bathe just because he likes it, while it is really not necessary, he must be able to give up his own wishes. Because what is pleasant is not always good. What is pleasant can also be harmful.

6. Be that as it may, if a fellow brother says that he is not feeling well, even though the illness has not yet manifested itself, believe him without question. But if you're not sure whether the care someone wants will help, call a doctor.

7. Always make sure there are two or more of you to go to a public bathing facility. This also applies if you have to go somewhere else. And do not choose the people who will go with you, but let the superior decide who will go with you.

8. The community will appoint someone to care for the sick. This person must also care for those who are on the mend and for those who are weak, even if they do not have a fever. The caregiver can get what he or she deems necessary from the kitchen for them.

9. Whoever is responsible for food, clothes or books should serve his fellow brothers without grumbling.

10. You can pick up the books every day at a set time; outside that time they are not available.

11. On the other hand, whoever is responsible for clothes and shoes should not delay giving them to those who need them.

Chapter VI

1. Don't argue, but if you do, end it as soon as possible. Otherwise, a little anger will turn into hatred, a mote will become a beam (Matt. 7:3-5), and you will turn your heart into a pit of murder. For it is written: “Whoever hates his brother is a murderer” (1 John 3:15).

2. If you have hurt someone by cursing, cursing, or accusing him rudely, remember to repair the harm you have done as quickly as possible by apologizing. And the other person who was hurt must in turn forgive you without wasting too many words. If two fellow brothers have offended each other, they must forgive each other their guilt (Matt. 6:12). Otherwise your praying of the Lord's Prayer becomes a lie. Besides, the more you pray, the more honest your prayer should be.

It is better to sympathize with someone who is quick to anger, but who immediately makes amends as soon as he realizes that he has wronged another, than with someone who is less quick-tempered, but has difficulty in apologizing. However, anyone who never wants to ask for forgiveness, or does not do so from the heart (Matt. 18:35), does not belong in a monastery, even if he is not sent away.

So beware of harsh words. If you have lost them, do not be afraid to speak the healing word with the same mouth that inflicted the wound.

3. However, it may happen that the necessary care for the proper course of events forces one of you to use harsh words towards minors in order to call them to order. In that case, you are not required to ask their forgiveness, even if you feel that you have gone too far. For if you behave too submissively towards these young people through excessive humility, this will undermine the authority that should guide them and to which they should submit. In such circumstances, you must ask forgiveness from the Lord of all who knows how much you love your fellow brothers, including those whom you may have been too harsh. Your love for each other should not remain stuck in self-love, but should be led by the Spirit.

Chapter VII

1. Obey your superior (Heb. 13:17) as a father, but also with the respect you owe him because of his task, otherwise you will do wrong against God in him. This applies even more to the priest who cares for all of you.

2. It is primarily the superior's responsibility to ensure that everything that has been said here is observed and that transgressions are not passed over carelessly. His job is to point out mistakes and correct them. Whatever exceeds his authority or power he will submit to the priest, whose authority in certain respects is greater than his.

3. Those who hold a government position should not seek happiness in the power with which they can dominate (Luke 22:25-26), but in the love with which they can serve (Gal. 5:13). By your esteem he will be your superior; because of his responsibility before God he will feel the least of all. He is to be an example to all in good works (Tit. 2:7); he will rebuke those who neglect their work, give courage to the discouraged, support the weak, and be patient with all (1 Thess. 5:14). He must himself honor the guidelines of the community and ask respect for them from others. He must seek to be loved by you rather than feared, though love and awe are necessary at the same time. He must always remember that he is responsible for you before God (Heb. 13:17).

4. By lovingly obeying you show that you have compassion not only for yourself (Sir. 30:23/24), but also for your superior. Because it also applies to your community: the higher you are placed, the more danger you run.

Chapter VIII

1. The Lord grant that you, seized by the desire for spiritual beauty (Sir. 44:6), may maintain all this with love. Live so that through your life you spread the life-giving good aroma of Christ (2 Cor. 2:15-16). Do not live as slaves under the law, but live as free people under grace (cf. Rom. 6:14-22).

2. This booklet should be read aloud once a week. It is like a mirror: you can see in it whether you are neglecting or forgetting anything (James 1:23-25). And if you find yourself answering to what it says, give thanks to the Lord, the giver of all good things. However, if anyone finds himself at fault, he should regret what has passed and beware of the future. He must pray: "Forgive my trespasses and lead me not into temptation" (Matt. 6:12-13).