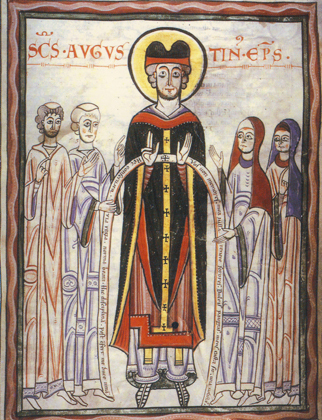

Augustine's spiritual legacy

The spirituality of Augustinians can be summarized in four words: interiority, prayer, community and pastoral care. Interiority is the conversation you have with yourself before God. It is precisely the relationship with a person who is the other, and God the Other, that makes you know yourself. In prayer you connect with God, in conversation with Him. It is a questioning or praising conversation, alone or in community with others. The community to which you belong is the place where God is found. Whether it is the community of the country you belong to, your church or your religious community. In each of these we have to accept the other as he or she is, in love. Pastoral care is an expression of the appeal that the church can make to us. Talents are there to be used. The opportunity to be a priest as an Augustinian also expresses your service to the church and the world. But behind these four core values lies Augustine's entire world of thought. We want to bring this into the spotlight. We cannot cover all aspects of Augustine's thoughts and spirituality here. We limit ourselves to a few important themes.

The primacy of love

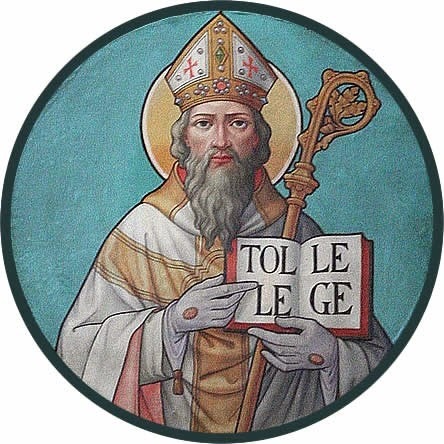

Augustine's oeuvre begins with the question of how a person can find true happiness. There is no one who does not desire to be happy. But desire has to do with love, for no one desires what he does not love. Love consists in wanting to become one with the loved object. But not every object that one loves makes one happy. Only an eternal and imperishable good can make us truly happy, for only such a good precludes any fear of losing what we love. Therefore, only God can guarantee such happiness. Love unites us to God as our eternal and lasting good. This happens according to the principle that a person becomes what he loves: "If he loves the earth, he will become earth; if he loves the eternal God, he will share in God's eternity."

Love: the whole message of the Bible

According to Augustine, the entire message of the Bible can be summarized in two commandments: love of God and love of neighbor. He writes: "My hope in the name of Christ is not barren, for not only do I believe, my God, that on these two commandments of love depend all the Law and the Prophets, but I have experienced it, and I still experience it every day, that no mystery or obscure word of Holy Scripture may become clear to me unless I encounter these two commandments." Here Augustine is the faithful echo of Paul's teaching: Love is the fulfillment of the Law (Rom. 13:10) and: The purpose of the commandment is love (1 Tim. 1:5). The word "end" does not mean that love ends or abolishes all other commandments, but rather that love is the perfection to which all other commandments point and can be restored. What has been said here about love applies to both the Old and the New Covenant. Therefore, Christ's words "A new commandment I give to you: Love one another as I have loved you" (John 13:34) renewed not only the apostles and us, but also all the patriarchs, prophets and righteous people who lived in the period of the first covenant.

To love with the love of God

By revealing himself as good and merciful, God reveals himself as love. For us this means a call, a demand and a commandment to love people as God loves them. The highest form of love for our brothers and sisters is to love them with God's love given to us through the Holy Spirit. Thus our love is a participation in the love of God that extends to every human being, even to our enemies. Our love must reflect God's love.

When Augustine speaks of love, he means love as a divine gift that endows our will with a new desire: a pursuit of divine truth, wisdom, peace and justice. To love with that love excludes all that is sinful, namely all possessive or selfish love, pride, presumption, and one's own praise, one's own honor, one's own advantage. The fact that love is a gift from God refers first and foremost to our love for God because He alone can give Himself to us. He loved us first. Secondly, this principle applies to our love for our neighbor. The Holy Spirit within us ignites our love for the person next to us.

For Augustine, a purely natural love for each other is not enough, because then we too easily neglect God as our highest good. Loving others as ourselves means that they may also find their good where we find it, namely in God. That is the most we can wish for each other. Only in this light can we correctly understand Augustine's famous statement: "Love, and then do what you want, because from that root nothing but good can spring." Love is the most difficult law we have been given; After all, it means that we are never free to just do what we want without taking others into account.

The temporary primacy of charity

By temporary priority we mean that here on earth, as long as we have to care for our fellow human beings, charity precedes love for God. It is true, says Augustine, that love for God comes first as a command, but equally that love for neighbor comes first in the order of execution. To love God we must begin by loving our neighbor: "These commandments you must always think about, you must weigh them, you must hold them, you must act on them, you must do them. Love of God comes first in the order of commanding, but love for neighbor comes first in the order of action. By loving your neighbor and being concerned for him or her, you continue to make progress. Where would you go unless to God the Lord?".

The reason why this is so is the fact that both loves enclose each other and cannot be separated from each other. Therefore it is sufficient to mention only one of the two commandments.

Appealing to the authority of Paul and John, Augustine draws the conclusion that it is not without reason that Sacred Scripture usually mentions only one commandment instead of two. Augustine himself gives the reason: "Why does Paul only mention love of neighbor in both Galatians and Romans? Isn't that because people can deceive themselves about love for God, since that love is not so is often put to the test? But with regard to love for one's neighbor, a person can much more easily be convinced that he does not love God when he treats another unjustly. Through the precept of charity one is made aware of one's own faults. Some Galatians deceived themselves into thinking that they loved God. It was clearly shown that this was not the case because of the hatred among brothers and sisters." Thus, charity is the standard for our love for God, because through its concreteness it excludes all self-deception. Love of neighbor is the most concrete means of expressing our love of God.

The Total Christ

Together one Body

“If in Scripture the only word of the Holy Spirit were that God is love, that would be ample and we would have to look no further.” The main reason for the Incarnation was the love of God through which He gave us His Son. Thus the Son became the incarnation of God's love. If God is love, then it follows that God did not wish to remain alone without any relationship with the world. Love requires community. God the Father produced an only Son, but did not want His only Son to remain alone. God gave Him all human beings as brothers and sisters. Christ stands in an inclusive relationship with all humanity, because his love extends to every human being without exception. In love we always discover two movements: the desire to become one with the loved one and the need to maintain a certain distance out of respect for the identity of the loved person.

Love results in a reciprocal presence without destruction of the other. Thus a friend is present in a friend, a man in his wife, a mother in her child. Christ also identified himself with every person and is present in everyone. Augustine called this union: the total Christ. In doing so, he relies on Paul's teaching of the relationship between Christ as head and the church as body: "Just as the body is one and has many members, and all the members, however many, form one body, so also the Christ" (1 Cor. 12:12). The one Christ includes both the head and the limbs, and this union is as intimate as the union in a living body. Thus Christ participates in our lives, and we participate in the life of Christ.

Honor God in each other (Rule of Augustine)

Because God is the center of Jesus' life, many of the ideas just mentioned are also applicable to God. The way to feel one with every person is to feel one with him or her in a higher unity, namely in God's care for all. God is present in every person. Everyone belongs to God who loves all. If we also love all, then we honor God. Only when people become each other's sisters and brothers do they form the new temple of God, that is, the place of his presence, for God dwells nowhere other than in love. Before we speak of a church as God's dwelling place, we must look at ourselves: "This church building is the house of our prayer, but we ourselves are the real house of God. Only when we are united in love do we together form the house of the Lord." The love of God and the love of man are therefore not competing actions, but embrace each other in one great dynamic movement.

Christ in the poor

Augustine finds his inspiration mainly in two texts: "Lord, when did we see You hungry and feed You, or thirsty and give You drink? And the king will answer: Amen, I tell you all that you did for one of the least of mine, you did it for me” (Matt. 25:37-40) and “Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?” (Acts 9:4). Regarding this last text, Augustine explains that the risen Christ does not say: Why do you persecute my disciples?, but rather: Why do you persecute me? This identification of Christ with the poor, the oppressed, the outcast and the persecuted meant for Augustine the recognition of their human dignity. For him, saying “Be faithful to your neighbor in his poverty” is like saying “Be faithful to Christ in his poverty.”

Mat. 25 shows how Christ is still present in this world and how He wants to be understood by believers. The suffering and poverty of Jesus Christ is constantly reflected in the lives and histories of suffering and oppressed people. Here during this pilgrimage on earth one feeds the hungry Christ, one gives drink to the thirsty Christ, one clothes the naked Christ, one welcomes Christ in the stranger, one visits Christ in the sick person. Where people are in need, Christ is in need. "Go into the streets. Christ, the stranger is not absent. Do you think that you are not allowed to welcome Christ? You ask: how is it possible to welcome Him? Listen. 'What you did for one of the least of Mine , you did for Me'. He who is rich is in need until the end of time. He is really in need, not in Himself as Head, but in His Limbs."

Option for the poor

“We are the servants of His Church, and especially of the weakest members of the Church, no matter what kind of members we ourselves are in that body.” This observation of Augustine clearly shows his deep concern for the poor and powerless. Some of Augustine's newly discovered letters give us more information about his social efforts. He asks the emperor to issue a new law against slave traders. He shows great concern about the sale of children; what is their fate? The Christian emperors had allowed them to be sold to prevent infanticide if the parents were unable to feed their babies, but then those children had to be released after a period of twenty-five years. Tenant farmers in particular desperately resorted to renting out or selling their children. This often led to permanent slavery and Augustine therefore protests against the abuse of children.

As bishop he also cared for orphans and took measures to ensure that they could not be robbed by strangers. He provided admission and shelter for abandoned children. It was the custom of the Church of Hippo to help the poor no matter who or what they were: non-Christians, prostitutes or fighters in the arena. Augustine says that he disagrees with the text "Be kind, but do not help the sinner" (Sir. 12:4-7) and then gives his opinion: "Let us treat them with human dignity, for they are human beings ."`

Friendship and community life

Value of friendship

Augustine had a very sociable and friendly character. He never wanted to be alone, and there was virtually no time in his life when he was without friends or relatives around him. In the ancient church there was no thinker who was so concerned with understanding human relationships. Even in his youth he laid the foundation for a number of lasting friendships. A beautiful passage from the Confessions describes this as follows: "In my association with friends there were many things that made my heart glad: talking together, laughing together and treating each other with kindness, reading beautiful books together, joking together and being serious, sometimes disagreeing with each other without bitterness, just as one sometimes disagrees with oneself, and then with that rarely occurring disagreement season the almost steady unity, teach each other something or learn something from each other, miss those absent with grudging and welcome those who come home with joy. These and the like signs that come from the hearts of those who love and give love in return, and which are reflected by countenance, tongue, eyes, and a thousand other traits of cordiality, were like fuels that welded our hearts together, so that many hearts were melted into one.”

This was what he loved in his friends. He felt guilty when he did not love the person who loved him, and when that love went unrequited. To love and be loved, to give love and receive love, that is, reciprocal love, that was Augustine's definition of friendship. The measure of true friendship is not temporary advantage, but unselfish love, based on a certain similarity of character, ideas, interest and commitment.

Limits of human friendship

Human nature possesses two great natural goods: marriage and friendship. In another text, Augustine declares that two things are essential to man, namely life and friendship, and that both are natural gifts. God created man so that he could have existence and live. But in order for people not to be lonely, there also had to be friendship. Anyone who would try to forbid all friendly intercourse must be aware that he is destroying all relations between people.

Loyalty, trust, truthfulness and stability are the most important qualities of friendship. All human affairs are impermanent; Augustine became most aware of this at the death of a childhood friend. The loss of that friend did not drive him to deny the value of friendship, but it did show him how friendship must be based in love for God because "only he does not lose a loved one because he is loved in God whom one cannot lose ". Not only death can tear a friend from our side, but also weakness and inconstancy can turn a friendship into deceit, baseness and even hatred. That is why Augustine seeks a basis of faithfulness and steadfastness for friendship in God and Christ. He endorses Cicero's definition of friendship: "Friendship is an agreement concerning all things human and divine, accompanied by goodwill and love." Cicero therefore did not exclude the deeper dimension of friendship.

Friendship within religious life

Unlike many founders of religious communities, Augustine gave an important place to friendship in the life of the community. He taught his young monks that they were not obliged to immediately include everyone in their friendship, but that it should be their wish to live in friendship with everyone. They had to interact with others in such a way that that possibility remained open. Even though we will never succeed in penetrating the very depths of another person, Augustine nevertheless draws attention to the fact that "One really knows no one except through friendship." When his monks asked him when they could call someone a friend, he replied: "We can call another person a friend if we dare to confide to another our innermost thoughts." For himself, he considered friendship a help and a consolation even in the monastery: "I confess, I easily throw myself completely into the love of my most trusted friends and without worries I rest in her, especially when I am tired of scandals of this world. For I feel that God is there, and in Him I cast myself securely and rest securely. In this certainty of love, I do not fear the uncertainty of tomorrow, the uncertainty of human frailty, about which I spoke earlier. I have complained in this letter ... What I entrust of my ideas and thoughts to a faithful friend, who is filled with Christian charity, I do not entrust to a human being, but to God, for that human being resides in God and is faithful through God".

The influence of Augustine's ideal of friendship

In Western Europe, especially in England and Northern France, we note a major influence of Augustine's concept of friendship on medieval religious life, and in particular on that of Cluny and the Cistercians. Here the names of Petrus Venerabilis, Bernard of Clairvaux, Aelred of Rievaulx, and Petrus of Celle appear. Apparently it was only in the fifteenth century that people wanted to banish friendship, because it was believed that friendship among religious undermined the integrity of religious communities.

Contemplation and action

Mixture of both

In his book The City of God, Augustine discusses three ways of life: the contemplative, the active and a mixture of both. His preference is for the hybrid form, contemplation combined with public office. No one should be so absorbed in contemplation that he no longer considers the benefit of his neighbor; nor should one be so absorbed in action as to neglect the contemplation of divine truth. Contemplation is not merely an intellectual activity, for it consists in loving and seeking God; and in such a way that the seeker does not keep the fruit of his or her contemplation for himself or herself without sharing in it with others. Thus the contemplative life has its own responsibility. Even the purest contemplation cannot be regarded as totally detached from all activity.

The active life as a greater danger

The selfless character of the religious life must be explicitly present in the active life, which must never be a form of self-seeking. It must always contribute to the well-being of others. In the text from The City of God, Augustine reflects something of his own evolution. He preferred a life of exploration in the Lord's treasury "as nothing more pleasant and nothing better," free from the commotion around him. Nevertheless, he was confronted with popular demands to accept active office, because "an abundance of injustice cools the love of many."

In his view, pastoral ministry posed a greater personal danger because it could easily be exercised in a superficial manner and spoiled by flattery. He knew a number of bishops and had often severely criticized them, because he considered himself more learned and better than them. From the moment he saw the priesthood as a public and social office, he was faced with the question of how he could offer his own faith to others for their salvation, without seeking any personal benefit, but only for the benefit of the great multitude. He did not wish, he says, to be a bishop who sits on his throne like a scarecrow who fulfills his task by standing motionless in a field.

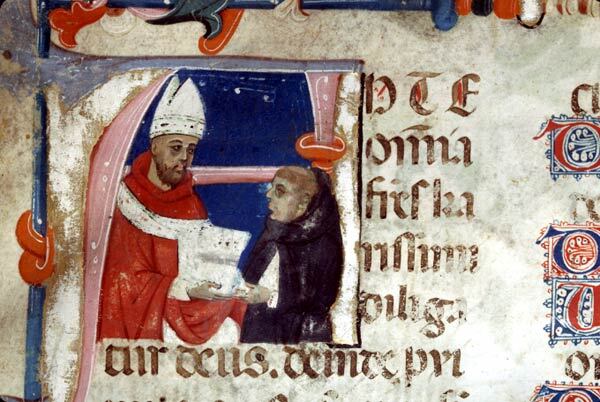

Christian and servant

Augustine always makes a distinction between being a Christian and holding a pastoral task. He is a Christian on his own responsibility for himself, but he is a pastor to serve the interests of others. Since the task of both, the cleric as well as the believer, is primarily to be a good Christian, there is no absolute division between the two. Augustine always tells his people: we too are together with your sheep; I am your fellow servant, your fellow worker in the Lord's vineyard, your fellow student in the same school of Christ. In one of his sermons he says very clearly: "What do I want? What do I wish? What do I desire? Why do I speak? Why do I sit here? Why do I live? Only with this intention: that we may live together with Christ. That is my desire, my honor, my joy and my wealth. For I do not want to be saved without you." The ordained office is therefore not a matter of honor or power, but of service. The expression "servant of the servants of Christ" later used by the Popes dates back to Augustine. His favorite description of the ordained office was invariably "burden", the burden that a soldier had to carry on his back. The apostolate is a ministry of teaching rather than commanding, of exhortation than of threat. Moreover, we should not lose sight of the fact that Augustine always describes the task of a priest or bishop as follows: he is a minister of word and sacrament. This order is not a mere coincidence, for he was convinced that the proclamation of the word was a more difficult task than the administration of the sacraments.

Mary and Martha

However important pastoral work, undertaken out of love for God and neighbor, is, it cannot be accomplished without a life of contemplation, prayer and study. A good pastor must first be a good hearer of the word before he can speak it. He must live as he speaks, and speak as he hears. Listening to the divine word is an aspect of contemplation. On the heights of the mountain the pastoral worker, like the apostle Peter, will receive light and spiritual food to distribute to others. For Augustine, the charming and beautiful Rachel is the image of a contemplative life, and the visually impaired, but fertile, Lia is the image of the toiling preacher. In the same way, Mary is an image of contemplation and Martha of pastoral work. But we should not forget that Augustine refuses to record Jesus' words to Martha: "Martha, Martha, how anxious and troubled you are about many things... Mary has chosen the better part" (Luke 10:41-42). take it as an accusation. "How could Jesus reproach Martha, who was happy to receive such an exalted guest? If this were a reproach, there would be no one left to care for the needy. Everyone would choose the best part and say: let spend all our time listening to the word of God. But if this were to happen, there would be no one to care for the stranger in the city, or anyone who needs bread and clothing, no one to care for the sick to visit, no one to free prisoners, no one to bury the dead. Works of mercy for those in need are a necessity here on earth."

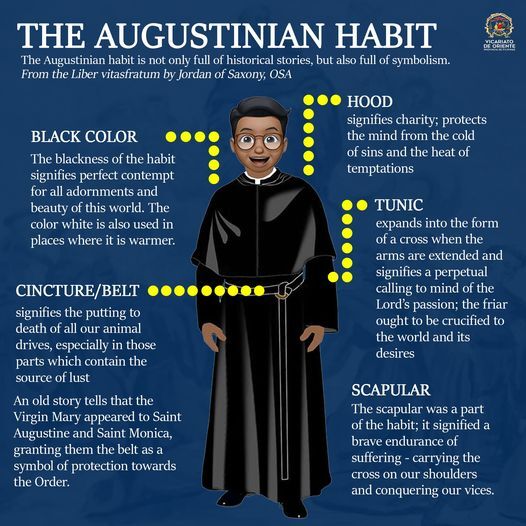

Don't dress to show off: the habit of the Augustinians.

Augustine's Rule states: do not dress conspicuously. Yet the Augustinians, like all other ancient religious orders, wear their own habit. How is that possible?

In Augustine's time there was no distinct religious dress of his own. The few monks in that time wore the simple clothing of their time, sometimes in black as a sign of mourning and renunciation of the world. When Augustine writes in his Rule that one should not dress conspicuously, he is not talking about specific religious clothing. He probably points to the wandering monks who deliberately looked unkempt, with long hair and worn-out clothing to show their disgust for the world.

During the time in which the Augustinians emerged, there were many new religious movements. The church was committed to ensuring that everything went smoothly. A much stronger distinction was made between a religious life and that of the 'ordinary' Christian. Moreover, people also wanted to know which order you belonged to, each with its own organizational structure. The original habit of the Augustinians was not black but white. They wore a white habit with a white scapular and a white hood. It was held together by a long belt that reached the ankles. That long belt is the real distinguishing mark of Augustinians. Over this white habit, friars wore a black covel with long sleeves and a black hood in choir prayers or outside the convent. In old frescoes or drawings you can still see how the lower habit protrudes from under the black covel. Since the Dominicans wore almost the same white habit and they originated earlier than the Augustinians, the Augustinians were not allowed to wear white where there were Dominicans in the city.

Over time the white under habit disappeared. In some Augustinian provinces, such as the Belgian one, until the 1960s, the old white underhabit was worn by novices. Over time, the long sleeves also disappeared. Until the 1960s, these sleeves were still used for preaching or official occasions. Then loose sleeves were slipped over the regular habit. In the 18th century the hood became larger and reached the front to the navel. From now on, the black habit would also become normal daily wear. Augustinians who were priests, unlike other mendicant orders, were given the right to wear a bonnet. This is a square hat for priests. The only difference was that the hat only had three wings instead of four, and no ball on the top. This bonnet is no longer worn in the order.

Augustine's order is larger than just the Augustinians. There are also Augustinian Recollects, Discalced Augustinians and Augustinians of Assumption, better known as Assumptionists. These differ in details from the habit of the Augustinians. The Recollects wear a shorter hood and a belt with a buckle, the Discalced also have a shorter hood and wear a rosary on their belt. The Assumptionists are indistinguishable in their habit from 'ordinary' Augustinians.